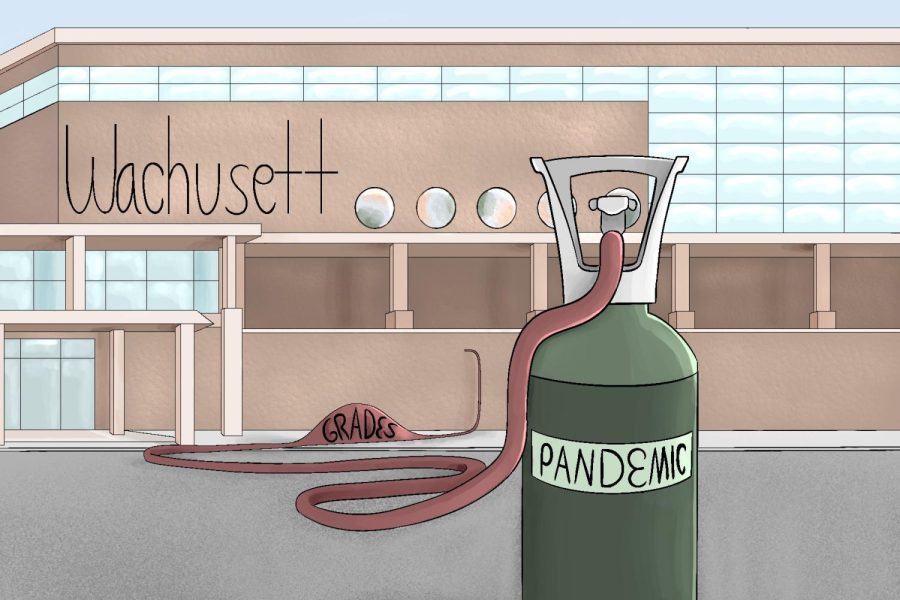

A for effort: student grades affected by Pandemic

A for effort? Grade inflation affected students across the country during the years of the pandemic. However, in this school year, students at the regional face new standards and expectations after two years of covid restrictions.

According to the The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, schools and colleges were advised to grade with compassion and grace during the pandemic. However, some teachers at the regional said that this has translated into a disadvantage for students after they have returned to in person school. Are the past years of remote learning coming back to haunt students?

Social studies teacher Tess Hickey referred to her remote policies as “forced compassion.”

“We were encouraged to give kids higher grades for less effort,” she said. “But now, that has transferred to kids and parents expecting higher grades for less effort.”

During the pandemic, many teachers, including Hickey, forewent tests and quizzes in favor of long-term projects to assess cumulative knowledge. However, some teachers and students express concern that this new assessment method may have resulted in poor study habits and information retention.

Junior Sage Swayze agreed that she “did not study” while remote. Swayze also stated that her grades have marginally lowered since returning to school.

“[During remote learning] the tests were easier and we had more time to complete assignments because there were less classes per day,” said Swayze.

In addition to changing class formats and schedules, the transition back to in-person schooling has taken its toll on students in other ways that may impact their grades.

According to Swayze, the return strained her sleep schedule.

“I get less sleep, I am more tired throughout the day leading to a shorter attention span and I am focusing on staying awake rather than the material we are supposed to be learning,” she said. “Also when I am tired I take longer to complete assignments.”

Guidance counselor Brittany Hanna agreed that remote learning took its toll on students’ executive functioning abilities.

“Students need increased support, especially with time management, motivation, and keeping up with the accelerated pace of being in the classroom,” Hanna said.

Other students have not seen a uniform increase or decrease in their grades, but rather a general fluctuation. Junior Avery Heppenstall, sees both the advantages and disadvantages to the return to in-person classes.

“Being at home made test anxiety for me less severe because I was in my own environment and felt more relaxed in tests,” said Heppenstall.

Teachers note that remote learning created challenges and hurdles for teachers and students alike.

“Remote learning happened so quickly, and often the expectations were unclear due to a lack of communication, so for that reason I feel that it was more difficult for students to succeed while remote,” said science teacher Dr. Cynthia Sparks.

Hickey said student participation also affected teacher and student success during remote learning.

“There was a great lack of participation during remote learning,” Hickey said. “So students certainly did not get the same class experience that they would have gotten had they been taking my class in school.”

Diminished student engagement was not only frustrating to teachers, but also a disadvantage to students.

“In in-person learning, I am able to connect things I learned to something said in class which can be helpful in tests and quizzes while in remote, no one really spoke in class, so that was more difficult,” Heppenstall said.

Both Hickey and Sparks concur that their teaching style during remote learning bled into the 2021 – 2022 school year.

“During the transition I found myself being more lenient with late work and project deadlines,” Sparks said.

Hickey agreed, but says that she is trying to return to the prior rigor of her class.

“During the first semester I was certainly still affording kids some benefits from remote learning, but during the second semester, I really tried to revert back to how I taught before the pandemic,” Hickey said.

The return to in-person school sprouts concerns from students and teachers about the transition and adjustment, and Hanna believes that students are in need of extra support during this time, stating that, unless their basic needs are met first, they will not succeed academically.

“We need to slow down and take a step back, we need to focus on students’ needs and overall well being so they can be the best learners they can be,” said Hanna. “It is difficult to focus and perform our best if there is an unhealthy level of stress and if we don’t feel safe or comfortable.”

Heppenstall speaks to the transition’s effect on her grades and habits.

“It was definitely an adjustment, and my grades showed that, but now I feel like I’m back on track to where I was pre-pandemic, in terms of grades and study habits,” said Heppenstall.

Hickey has lingering concerns about trends in student advancement through grades and courses.

“I worry that, due to the 2000-2021 year being almost a ‘non-year’, that many students were pushed forward into advanced classes without their prerequisites being met due to the leniency in grading,” said Hickey.

Hanna sees a trend emerging in conjunction with the return to in-person schooling, as an increased amount of students are filling out class reconsideration forms.

“Students are having a hard time figuring out what levels are best for them, and we are trying to have more meaningful conversations about their access to and understanding of the curriculum,” said Hanna.

The return to in-person school comes with ups and downs, but it is happening, whether students and teachers like it or not.

“It’s time to push kids back to normalcy,” says Hickey. “The attitude many students have that they can do less and expect to receive the same grades that they got during the pandemic is just unrealistic.”

Ella is a junior and this is her second year writing for the Echo and first year as Editor of Editorials and Features. In her free time, Ella enjoys...

Sammy Lane is the Illustration Editor for the Wachusett Echo.